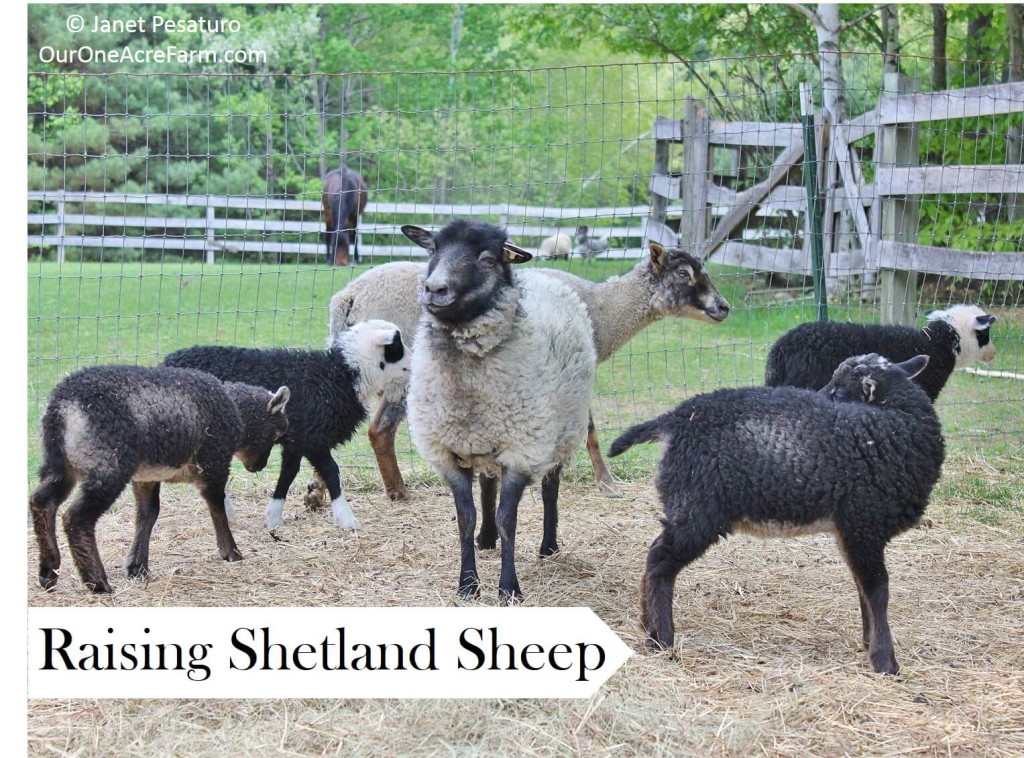

A flock of Shetland sheep at Wild Air Farm in Bolton, Massachusetts enjoying a beautiful spring day.

This small, hardy, heritage sheep breed is a great choice for a small farm, whether you’re interested in a few sheep as pets, and/or a source of fiber, meat, or even milk. The soft but slightly crisp feel, and the rich variety of natural colors make Shetland fleeces in demand among hand spinners, knitters, and weavers. As a passionate knitter, I longed to raise Shetland sheep for years…Alas, time, money, and space have been used for other endeavors, and Shetlands are probably not in my future. I learned a lot about them during my years as a fiber festival junky, but because I don’t have first hand experienced raising Shetland sheep, I interviewed our neighbors right here in Bolton, Massachusetts: Montana and Carol Airey of Wild Air Farm. A bit of vicarious shepherding on my part – hopefully the information and photos of their beautiful farm will help and inspire you.

Raising Shetland Sheep

A word of caution to start with. While these sheep are small, they are still sheep and may not be permitted in your backyard. Don’t get your hopes up until you check the local laws and regulations for restrictions on types of livestock, limitations on numbers of animals, distance of structures from property lines, etc. Be aware of state and local wetland laws, for activity may be limited or prohibited within a certain distance from streams, swamps, vernal pools, etc. Ignorance is no excuse for a violation, and you may have to relocate your set-up or remove it entirely, even if you were unaware of restrictions.

Montana Airey chose Shetland sheep for their beauty, charm, small size, and gorgeous fleeces.

Wild Air Farm as an Example

As long time hobby homesteaders, the Aireys had horses, chickens, and a large vegetable garden for years before starting their flock of Shetlands. Montana Airey, now an undergraduate at Boston University, decided that poultry just wasn’t enough, and thought sheep “would provide me with a more rewarding experience.” Indeed, it has been rewarding, as you can glean from her blog, Wild Air Shetlands. Check it out, and contact her if you are interested in purchasing fleeces or animals.

Montana chose Shetlands for their beauty, charm, small size, and gorgeous colorful fleeces. In her breeding program, she selects for “sound bodies, kind personalities” and soft fleeces in shades of gray to black, with a medium to loose crimp. Carol, her mom, uses the fleeces for hand spinning and weaving.

They keep 4-5 breeding ewes, two yearling ewes for showing, and a ram. To constantly improve their breeding stock, they occasionally replace older breeding ewes with yearlings. They do not keep rams over 2 years old, because aggression begins to rise by then. They usually get about 8 lambs per year, which both Montana and Carol show (and often win!). They keep 2 female lambs for future showing and breeding. The rest are sold or sent to the butcher.

Shetland sheep fleeces come in a range of natural browns and grays, as well as black and white. Some individuals are patterned, such as the “panda” lamb in front.

Breed Profile

- History – Probably brought to the Shetland Islands by Viking settlers. Shetland sheep are a “primitive” breed of naturally short tailed sheep that were largely displaced by long tailed breeds in Northern and Western Europe about 2,500 years ago. The short-tailed sheep were relegated to remote areas. By the late 1800’s all that was left of the short-tailed sheep was the Shetland type, on just a few islands, including the Shetland Islands. By the 1970’s, it was considered a rare breed, but since then its popularity has grown. The Livestock Conservancy considers it a recovering breed, so raising registered Shetland sheep contributes to heritage breed conservation.

- Physical Attributes – One of the smallest sheep breeds, and perhaps the smallest available in North America. Small, fine boned, and agile. Ewes typically achieve a weight of 75-100 lbs, and rams 90-125 lbs, according to the North American Shetland Sheep Breeders Association. However, some people select for smaller animals in their breeding programs, so you may be able to find significantly smaller ones. Rams have spiral horns, and ewes usually lack horns (i.e., ewes are “polled” in shepherd talk).

- Behavior – Shetlands have not been as intensively bred as other sheep used in large scale farming, so they have retained many of their ancestral characteristics: thrift, longevity, easy lambing, hardiness, and adaptability. Most people describe them as calm and easily managed. They wag their tails like dogs when petted, and can be walked on leash. But Carol and Montana emphasize that the behavior of any sheep, including Shetlands, depends on how they are managed. If you want them to calmly enjoy petting, you must handle them often as lambs.

- Fleece – Contrary to popular belief, sheep did not evolve with white fleeces requiring human shearers. Humans selected for those traits. Ancient sheep likely evolved with coats of muted earth tones for camouflage, and shed their coats annually. The Shetland is thought to be closely related to the wild ancestor of domestic sheep, as it retains those adaptive traits. See below under “Shearing” for discussion of this breed’s tendency to molt. Shetland fleeces come in a wide range of natural colors, including white, black, and many shades of gray and brown. The grays range from dusky blue-gray to steely-gray. Browns range from pale yellowish-brown, light grayish-brown, fawn, and dark brown. Some breeders focus on a specific color or pattern; others breed for variety. A Shetland fleece weighs about 2 – 3.5 lbs, and is considered a “down” wool, with fiber diameter of 23-30 microns, high elasticity (crimp), and low luster. But there is much individual variation. Some animals have looser, more lustrous wool. Classic Shetland yarn a full, round, springy, and chalky appearance. The elasticity makes it wonderful for hand knitting (one of my favorites), and helps the final garment hold its shape

- Meat – Shetland sheep are very small relative to “meet breeds”, but they do have a high muscle mass to bone mass ratio, giving a good yield of meat for their size. Shetland “lamb” is from animals less than 1 year old. This slow growing breed produces a delicate flavor even in older sheep. Meat from 1-2 year old Shetland sheep (called a “hogget”) is more flavorfu, but delicate enough to be cooked as lamb. Meat from older Shetland sheep is considered mutton, and is usually marinaded and slowly cooked.

- Milk – The Aireys don’t milk their sheep, but Shetlands can be milked. Search online communities to connect with people who’ve done it. One flock mistress described milking her Shetlands as follows: Separate the ewe from her lamb until the latter begins to cry. Then milk the ewe and reunite her with the lamb. The ewe can be haltered and given grain during milking, just like a goat. That flock mistress got 1.5 quarts of milk per day, while the ewe was nursing her twins.

As a hand spinner and weaver, Carol appreciates the range of natural shades of Shetland fleeces.

Buying Shetland Sheep

Because sheep are flock animals, you need at least two of them to satisfy their social needs. Before buying, determine your goals with the animals, because you need to know whether the expense of registered Shetland sheep is worth it. Get registered sheep if you want to contribute to breed conservation, or if you want to breed them seriously. Be aware that while breeding quality offspring of registered animals will command higher prices, their meat or wool will not. Want a few sheep for pets and fiber that you won’t be breeding? Then un-registered Shetlands, or even hybrids, are fine.

To find your sheep, search online and attend Fiber Festivals. See the Sources at the end of this post, for a calendar of fiber festival events. Whatever you do, avoid livestock auctions, where many of the animals have serious health problems. Montana suggests that you look for “bright eyes, energy, and perked ears…don’t pick any sheep with weird legs or weak backs.”

If you are looking for good quality fleece, educate yourself on fleeces. “Go to shows or fiber festivals and get your hands on prize winning fibers,” Montana advises. The book “In Sheep’s Clothing” in “Resources”, below, has invaluable information on sheep’s wool in general, and fleece by breed.

Attend fiber festivals to learn to recognize quality and appreciate variation in Shetland fleeces. This ewe was shorn earlier in spring, and already her fleece is long. For a Shetland, she has an unusually long and loose fleece.

What You Need for Your Shetland Sheep

Though Shetland sheep are small and hardy, there are some basic necessities, as well as some conveniences that you might want.

- Shelter – Hardy sheep like the Shetland need only a 3-sided shelter with open side facing away from the prevailing wind. However, you (and the sheep) might appreciate a four-sided structure for protection from predators and extreme weather. The Aireys lock up their flock every night to keep them safe. If you do not lock yours up, you must have other excellent night time predator protection (see below). You do not need much indoor space if sheep will be outdoors most days. Good ventilation is a must.

Though the hardy Shetland can weather our New England winters with no more than a 3-sided shelter, the Airey’s lock their sheep up in this shed at night for protection from predators.

- Pasture – Mud is not a healthy substrate for sheep, so you’ll need a well drained site. More pasture space,

The Airey’s ram enjoys the 1 acre pasture where their horse grazes. When the ewes and lambs rotate into the pasture, the ram is hay fed in the smaller enclosure.

level land, and better quality grass mean less money spent on hay, and probably happier sheep. Beware that some plants are poisonous to sheep. You will have to learn which ones grow in your area, and remove them from your pasture. Because sheep can be hay fed, there is really no minimum pasture area per animal. The Airey’s have an interesting system that works well for them. Their sheep use 2 fenced areas: a quarter acre area where the animals are hay fed, and a one acre pasture shared with a horse. Their ram must be kept separate from the ewes and lambs, so the ram and the flock of ewes/lambs rotate between the pasture and the smaller enclosure.

- Fencing – Electric fencing makes it easy to keep sheep contained. It takes only one shock. The greater challenge will be excluding predators. Know which predators roam your region, learn about their behaviors, and talk with other flock masters about the best way to deter them. Here in Massachusetts, where coyotes and bobcats are common, and black bears are occasional, the Aireys find that 2 electric wires running along the lower portion of the fence keep their flock safe.

Good fencing and electric wires contain the sheep and exclude predators. Trees around the enclosure provide needed shade.

- Trees – Some shepherds of the desert southwest say all their sheep need for shelter are shade trees, which double as scratch posts (sheep like to rub against them). But sheltering tree canopies and tree trunk rubbing posts will be appreciated by sheep in any climate, and many flock owners consider them essential. If you have no shade trees, you will need shade structures during summer.

- Water – How far and how often do you want to lug buckets of water? You might do without a water line if you’ve got 3 sheep in a shed 30 feet from the house, but what if you have 10 sheep in a barn 200 feet from the house? And if you’re in a dry climate, you might need irrigation unless you don’t mind hay feeding most of the year.

- Bedding – There are many options for bedding, but it must be clean and dry. Saw dust and wood shavings are poor choices, because particles get stuck in the fleece. Straw and hay are better options.

Feeding Shetland Sheep

Hardy, thrifty Shetlands thrive on forage, but if you have insufficient pasture, or if you’re under snow during winter, you will have to supplement with hay for at least part of the year. Factor that into your budget. The Aireys’ sheep get hay to supplement their small pasture, as well as commercial sheep feed to ensure good nutrition. Montana and Carol are quick to point out that any commercial feed should be labeled specifically for sheep because sheep are easily poisoned by the higher copper content of pig, cattle, and some goat feeds.

Keeping the food clean is a must. Do not leave their feed hay on the ground. Sheep will not eat anything sullied by urine or droppings, and for good reason. Dirty feed can spread diseases and parasites. A horse style nylon hay bag is sometimes recommended as a good hay feeder for a few sheep. Don’t use a standard big bale feeder, because they animals can get a lot of debris stuck to their fleece as they stick their heads in the hay while feeding.

Once the hay is contaminated with urine or droppings, sheep won’t eat it. The hay on the ground here is fine for litter, but feed hay must be elevated to keep it clean.

Health Maintenance

Numerous ailments can afflict sheep, but you don’t need to learn them all from the outset. You should, however, be aware of a few common health care issues:

- Shearing – must be done in spring time, and in Shetlands, you should be vigilant for the onset of natural shedding. “Shetlands have a natural break in their fleece….and shearing should be done before the fleece breaks to ensure quality,” explains Montana. If you shear after the natural break begins, the fleeces will have last years growth, a break, and a little of the current year’s growth. But get to know your sheep. Some Shetlands shed fully, and if yours does, you can choose to wait for the break and pluck (or “roo”, as it is called). If you are going to shear, you will need a shearer (search the internet, network with local shepherds, or inquire at fiber festivals). Montana does it herself with electric shearers.

Spring shearing keeps this ewe cool for the summer.

- A vaccination program – must be tailored to your flock and geographic area. For example, Montana’s ewe’s get a CDT vaccine (for Clostridium and Tetanus) every year around lambing. Lambs get a booster sometime after birth, and then annually thereafter. You can administer them yourself, says Montana: “Specific instructions will be available through any vet, or on the medicine bottles if you prefer to do self vaccinations. Other vaccines, such as rabies, may be administered by vets. These are needed for showing (and) moving across state lines…”

- Hoof trimming – needs to be done at least once a year, usually more often, depending on what your sheep are walking on (soil type and moisture). Here in Massachusetts, the Aireys find that twice a year trimming is needed. You will need a pair of hoof shears, and you’ll need to learn to use them properly.

- Parasites – can be a problem for sheep. External parasites include flies, lice, and ticks. Various biting flies annoy sheep. Blowflies cause “fly strike” by laying their eggs in wounds, where maggots hatch and digest their host’s body tissue. A deadly systemic infection can result. I once lost a hen to fly strike; it’s no joke. Keep wounds clean until healed!

- Other contagious diseases are important to be aware of, explains Montana. Foot rot, pink eye, and sore mouth are common but preventable problems. “All of these issues can be contracted from other sheep, and if you do not have them within your flock you will remain free of them.” That is, of course, if you practice good bio-security.

Lambing

Wild Air Shetlands are extremely tame because they’re handled from birth. Lambs not handled frequently may become skittish.

Ewes can be bred to 10-12 years of age. Unlike commercial sheep which have been intensively bred for production, Shetland ewes have retained the ability to lamb with little to no human assistance. They have few problems, and the need to bottle feed a lamb is rare.

“Many times I have gone out in the morning and found lambs dried and running around, ” says Montana, but she advises close observation, nonetheless: “All sheep no matter how healthy they may seem can have health issues. It is vitally important to always be watchful of a ewe in labor/going into labor so any warning signs can be perceived and dealt with as early as possible.” Mark the words of a responsible shepherdess!

Protection from Predators

Dogs, coyotes, wolves, foxes, bears, cougars, bobcats, and eagles take sheep, especially lambs. You might not have all of those characters in your region; we don’t have them all. So learn which ones do prowl your area, and how to deter them. Read 10 Myths About Wild Predators to deepen your understanding of predator behavior. For their small flock here in Massachusetts, Montana Airey says that electric fencing during the day and predator proof confinement at night have prevented loss. But carefully evaluate your own situation to determine how best to protect your flock. Many sheep producers use guardian animals with great success. Here are the most commonly used ones:

- Dogs, such as the Great Pyrenees, bred specifically to guard livestock. About 75% of them will become excellent guardians, but they must be raised with the sheep, not as pets.

- Donkeys instinctively protect their companions from predators

- Llamas are an excellent choice. They eat the same feed as the sheep and require many of the same vaccinations. They their droppings all in one latrine (pile), and some of them have beautiful fleeces.

Montana demonstrates showing her sheep. Prize money from showing has been her most significant source of income in her ovine adventures.

Making Money

Raising Shetland sheep is mostly a hobby and educational experience for Montana. She has never calculated her expenses and income, but thinks her greatest source of income is the prize money she brings in from showing her sheep. “But I do a little bit more than just the average hobby farm because on some years I attend up to 9 fairs.”

You might find other ways to support a Shetland sheep obsession. Top quality fleeces and registered animals can bring in some money. Woven, knitted, or felted decor, and soap or artisan cheese made from sheep milk are possibilities.

Resources:

- Fournier, N. and Jane Fournier. 1995. In Sheep’s Clothing: A Handspinner’s Guide to Wool. Interweave Press, Loveland, CO.

- National Calendar of Fiber Festival Events

- North American Shetland Sheepbreeders Association

- Shetland Sheep Facebook Page

- Weaver, S. 2005. Sheep: Small-Scale Sheep Keeping for Pleasure and Profit. Hobby Farm Press, Irvine, CA.

- Wild Air Shetlands (blog of Montana Airey, who was interviewed for this post)

Pin this image!

Pingback: How to Start a Backyard Farm - One Acre Farm

Pingback: Raising Shetland Sheep: Guide To Starting A Flock

Pingback: What To Raise On Your Homestead or Backyard Farm - One Acre Farm

hi , i’m here in Northern Nichigan with aa small flock of shetland sheeep.

One ewe (2 years old) isn’t accepting her twins …..I will have to milk her and don’t know how ……

Could you give me some advice. please. Awaiting your answer a.s.a.p…..

Thank you so much in advance cordially Ida

Hey, I’m curious if you know of small sheep breeds that mix well with shetland.

I’m not very familiar with other small breeds. Sorry!

olde english southdowns or babydoll sheep as they are often referred as.they are small like shetlands and easy to handle

Hi, I’m only thirteen but thinking of getting some Shetlands in April (I’m in the UK) and I don’t know what age to get. If I get ewe lambs then I will be able to create more of a bond with them but I will probably wait until the year after to breed them which I don’t really want to do. If I get yearlings then I won’t know them as well or have a better bond, but I will be able to breed them in November 2017.

Also we are only going to be getting a small trailer but I don’t know whether to get 3 or 4? If so, what combination? Do I get three ewes and a ram or 4 or 3 ewes?

Thanks a lot, Phoebe

Hi Phoebe, if you want ewes so you can breed them earlier, I suggest you meet them and determine if they’re tame enough for your liking. The nice thing about lambs is that you can raise them to be really tame if you handle them a lot when young. As for whether or not to get a ram, obviously you need one if you want to breed them, unless you plan to breed the ewes with someone else’s ram. If so, does that ram have the qualities you want? If not, then perhaps you should get your own. Good luck!

Great information and well written. I will bookmark and referr back to it as I explore the possibility of adding a small flock of sheep to our farm. Do you happen to know anything about this breeds usefulness for underbrush control ? I have plenty of pasture but would like them to help my husband clean up and maintain the wooded area of our proptery.

The other breed that I have looked closely at is babydoll. Any thoughts?

Thank you for your time and the great article.

Tamara Andring

FYI I am in Bristol TN

Tamara, I am near Sparta NC, and am about to get a couple of Shetlands, still researching like crazy so when I pick them out (Wednesday) Ill hopefully be somewhat prepared… still feeling woefully under-prepared, its such a big decision!

Do you have a Shetland flock now? I see your comment was March 2017.

When is the best time to neuter a ram lamb? I have a 2 week old ram lamb who is being bottle fed. I know he cannot be used for breeding because of having been imprinted to humans, so we are going to use him as a pasture budding to the ram.

Swap his bottles for a bucket feeder and let him have contact with the sheep around him so that he knows he is still a sheep and learns the sheep ways.

Then he will be suitable for breeding.

As for being 2 week old..it is now too late to band him properly (if you are in the uk) it supposed to be done by day 11. There are other ways of castrating but only a vet or trained sheppard can do this. X

Does anyone shear twice a year – spring and fall?

Can a Spring lamb still be tamed if not handled as of yet as it’s already mid July

We got some breeding ewes and there was a lot of variety in their tameness. Being persistent and patient with bucket training has now got all but the most flighty ewe eating from the bucket and often from the hand too. Bizzarely, after they had lambs this spring that was a significant turning point for them coming to the bucket.

Most of the lambs eat from the hand too, but it varies on the “personality” of the lamb as to how keen they are.

I am getting ready to help a friend do routine CDT vaccination as well as ivermectin on their little Shetland herd. I was just curious if we had to administer the ivermectin via subcutaneous injection (they have the injectable version), or could we simply add it to the feed for oral administration? If so, I think the benefit of reducing the stress of time spent restrained and one less needle poke would be worth it!

CDT vaccinations are standard Springtime care for sheep, but Ivermectin alone is insufficient, as the parasites like meningeal worm have mutated/evolved a resistance. It does come in both injectable and oral forms, but we rotate it with Panacur or fenbendazole. There are many good sites with up-to-date research from universities that are extremely helpful.