Foraging Garlic Mustard. How to identify it, where to find it, and how to harvest this abundant wild edible plant.

This European native is one of the most maligned plants in the US. In many areas, garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) is controlled by pulling, poisoning, and/or burning, due to its invasive nature. Controlling it by eating it is rarely mentioned, but it is a cruciferous vegetable, in the same family as broccoli, cauliflower, and cabbage. And it may be more nutritious. If you’re already familiar with this plant and want a recipe, try my garlic mustard pesto.

For a nutritional analysis of garlic mustard, I give you the esteemed Journal of Food Biochemistry. In a 1999 study, Guil-Guerrero et al. studied the nutritional composition of 5 wild edible crucifer species, with A. petiolata among them. The vitamin C contents were high, and especially high (261 mg / 100 gm) in garlic mustard. Compare this to 93 mg of vitamin C per 100 gm of raw broccoli. Garlic mustard was also high in mineral elements, carotenoids, and fiber. The authors’ conclusion? “We believe these species of crucifers could be used for dietary purposes, due to the amount and diversity of nutrients they contain.”

Yet people destroy garlic mustard and dispose of it as a noxious, invasive weed.

How invasive is it? Earlier studies describe its ability to out compete native plants and inhibit their growth. But some of the more recent studies show little affect on other plant species (Davis et al., 2012) and declining ability to inhibit the growth of other plants, over time (Lankau et al., 2009). Maybe we jumped the gun on engaging in chemical warfare with this plant? I am no purist, but the fact that we pollute with herbicides, in an effort to reduce a nutritious vegetable of questionable environmental impact, boggles my mind.

So please join me in adapting to our changing environment. Transform garlic mustard into a useful resource. Its abundance may or may not be damaging, but in either case, we can reduce it and benefit from its nutrition at the same time. Help stop the chemical warfare and start cooking with garlic mustard. I can’t wait till some clever chef discovers its great culinary potential, and gets top dollar from unsuspecting patrons who don’t realize they’re eating a weed from the edge of the parking lot.

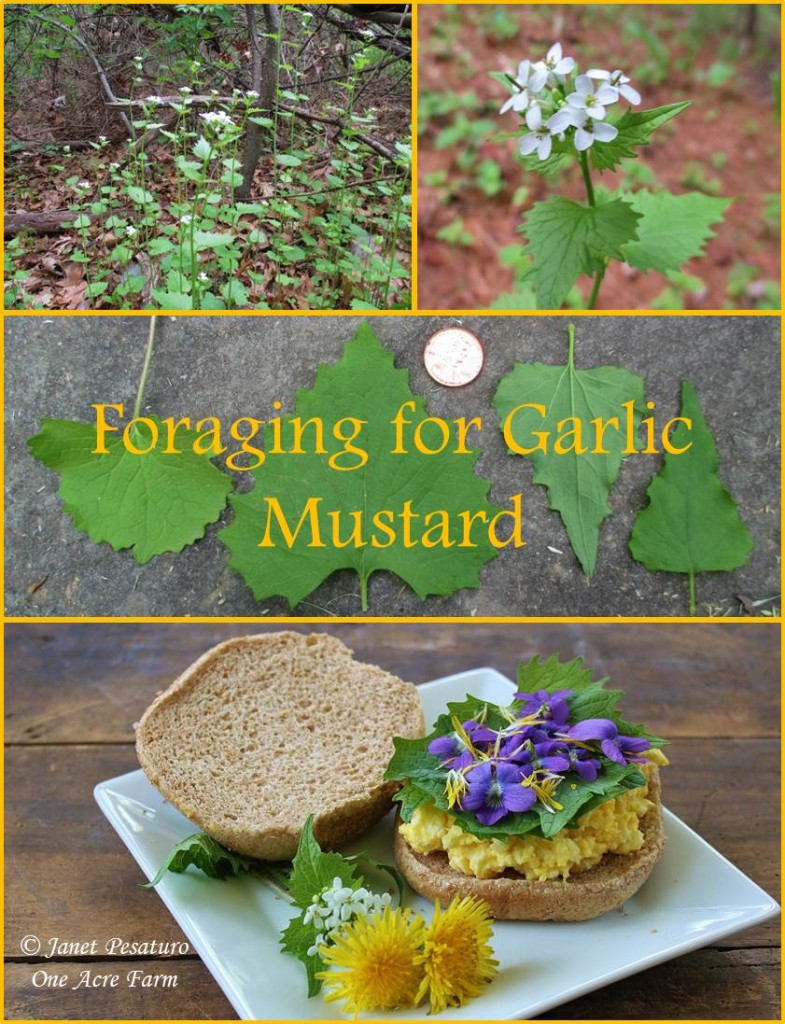

Foraging for Garlic Mustard. Photo shows a typical patch of this delicate looking plant topped with tiny white flowers.

Before I describe how to identify and harvest this plant, I want to emphasize how important it is to be 100% certain of identity before eating any wild plant. Be sure to consult several resources. Here are some of my favorites, which I use regularly:

Foraging garlic mustard: where to find it

This Eurasian native is now found in most of the eastern and mid-western US, and in Alaska, British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec, according to this range map. Within its range, look for it on roadsides, trail sides, other disturbed areas, and even in the forest understory.

If you are new to garlic mustard, the easiest way to learn to identify it is to find it in spring while it’s blooming. Here in MA, blooming begins in early-mid May. Look for a patch of a 2-3 foot tall, somewhat delicate appearing, herbaceous plant with a haze of small white flowers at the top, as in the photo above. Then examine the flowers and leaves to see if they match garlic mustard.

Identify garlic mustard flowers

The small white flowers are clustered at the top of the plant. Each bloom is about 1/2 inch in diameter and has 4 petals.

Identify garlic mustard leaves

Leaves are arranged alternately on the stem. They are approximately heart shaped, but vary according to where they grow on the plant. They are about 1.5 to 4 inches long. Lower leaves are like a heart with a blunt point, and scalloped edges. Moving up the stem, leaves become longer, narrower, and pointier, almost triangular, with toothed edges. The photo at right shows lower leaves. The photo below shows a basal leaf on the far left, and leaves taken from further up the stem as you move right.

Garlic mustard is actually a biennial plant, and in its first year appears as a rosette of the roundish, scalloped leaves that grow at the base of 2nd year plants. But you don’t really need to know this to forage for it, and it’s easier to find 2nd year plants.

Foraging Garlic Mustard. Photo shows lower most to upper most leaves, from left to right. Coin placed for scale.

Identify garlic mustard seed pods

By mid-late May, long, skinny 1-3 inch long seed pods appear at the top where flowers once were. Ripe seeds are dark and elongated.

Harvesting and eating garlic mustard

Stalks

Young stalks are said to be best if harvested just prior to flowering. I have not tried these, and descriptions of their flavor vary from author to author. Some say they are bitter when raw but sweeten after boiling. Others say they are the best part of the plant: sweet and broccoli-like in flavor, even when raw. Perhaps the flavor varies with site conditions, plant genetics, or taste buds.

Leaves

Here in MA, I have found that leaves are somewhat pungent (sharp and peppery, I would say), but not bitter, if harvested before any of the flowers have gone to pods (at which point they do become bitter). I have found this to be true of leaves I harvest in my area, whether the soil is poor and sandy, or deep and rich. I was pleasantly surprised at the flavor – shocked, even – based on what I’d read or heard from several others. Some people describe the flavor as quite bitter, even when young.

I’m sure it’s partly a matter of taste, but not entirely, as I am not very tolerant of bitter flavors. I wonder if the wide variation in flavor description has more to do with plant genetics, especially in light of the findings of Lankau et al. (2009). They found that phytotoxin declines with time, as the plant evolves, after invasion. Perhaps the bitter compounds decline as well.

I don’t think the leaves taste much like garlic, by the way. To me, they are similar to cultivated young mustard greens that are added to gourmet mixes of baby salad greens. Except garlic mustard grows in abundance all on its own, and is free for the taking.

One friend who does like it, suggested topping egg salad with garlic mustard leaves, and I found that delicious. It also works well on tuna salad, and in mixed green salads. It’s also makes a nice pesto – click here for my garlic mustard pesto recipe.

Foraging Garlic Mustard. How to identify, find, and harvest this wild edible plant. Young, raw leaves are excellent in sandwiches and salads. Here, I add violets and dandelion petals for a bit of sweetness.

Seeds

A friend of mine is working on a recipe for spreadable mustard using garlic mustard seeds. This is not something I have attempted, but look forward to her results.

Have you tried garlic mustard? Which part of the plant? How do you prepare it?

Sources:

- Davis, M.A. et al. 2012. The Population Dynamics and Ecological Effects of Garlic Mustard, Alliaria petiolata, in a Minnesotao Oak Woodland. A. Midl. Nat. 168: 364-374.

- Guil-Guerrero, J.L. et al. 1999. Nutritional Composition of Wild Edible Crucifer Species. Journal of Food Biochemistry. 23(3) 283-294.

- Kallas, J. Edible Wild Plants. Gibbs Smith publishing company, 2010.

- Lankau, R.A. et al. 2009. Evolutionary Limits Ameliorate the Negative Impact of an Invasive Plant. PNAS. vol. 106, no. 36.

- Thayer, S. Nature’s Garden. Forager’s Harvest Press. 2010.

Shared on: HomeAcre Hop #7, From the Farm, Natural Living Monday, Homestead Barn Hop #166, Mostly Homemade Mondays #87, Wildcrafting Wednesday #139

What an exceptional job! I love your attention to detail and how you cited your sources. Thanks for a blog to build confidence in food foraging.

Thanks for the kind remarks, Chaya!

Please be aware garlic mustard will crowd out basically any plant that is not a mature tree, and it will even keep those from repopulating! Eating it is certainly one way to try to keep it from spreading, but it needs to be contained so that it doesn’t destroy the ecosystem.

That is an exaggeration, based on old assumptions and incomplete data. At least in some situations, garlic mustard has little to no impact, and accumulating evidence suggests it is “more a product than an agent of change in eastern North American deciduous forest”. See Davis, M. A. et al. “The Population Dynamics and Ecological Effects of Garlic Mustard, Alliaria petiolata, in a Minnesota Oak Woodland.” The American Midland Naturalist. 168 (2012): 364-374.

Note that in the discussion section of that paper, there is reference to 7 additional studies showing “very small, inconsistent, or no negative effects of A. petiolata on other plant species in eastern North American forests and woodlands.” See the list of literature cited in the Davis et al paper, for complete citations of those 7 papers.

And my own personal experience: it has been at the edge of my property for years and years now, with little to no spread, and no choking out of existing plants.

Sounds interesting! Hoping to try the leaves sometime! I assume the flowers aren’t edible.

I have read that the flower buds are edible, but are “stronger” in flavor than stalks or leaves. I have not tried them, but given the wide variation in flavor descriptions of other plant parts, I probably should try them myself!

Perhaps this will my next foraging obsession! I’ve heard of Garlic Mustard, but have yet to find/identify/eat it. After reading this, my eyes will be open! As always, I appreciate your posts, as they are so helpful as I learn about wild edibles 🙂

Thanks, Rachel! I hope you do give it a try, and let me know what you think of it.

great article

Thanks, Bobbye!

Pingback: Garlic Mustard Pesto with Baby Spinach - One Acre Farm

Pingback: Weeds, Glorious Weeds! | ruthschickens

I LOVE Garlic Mustard! I use it in salads, in place of lettuce on sandwiches and of coarse as an eatable garnish. What’s better than Free and Nutritious?

That’s great, Sabrina! I am delighted to learn that others are taking advantage of this “noxious” weed!

Thanks for sharing at The Green Thumb Thursday Garden Blog Hop. We hope you will join us again this week.

I love to forage and I will be on the look out for some wild garlic mustard. Looking for the flowers will help tremendously.

Thank you, Tanya.

Thanks for your interesting article. Here in West Virginia, garlic mustard is pulled and burned because it out competes our native wild flowers. At the WVU Arboretum, there is an annual garlic mustard pull, and the areas which have been eradicated of the plant, are being filled with native flowers. Just like Autumn Olive, which is beautiful, it will take over. A changing world is inevitable, but the sad thing is that many native pollinators, such as butterflies, need these wild flowers to lay their eggs on, and get nectar from. Some birds need these insects for food, etc.. There is a delicate balance in nature, and I think this needs to be considered, so when one foes out to gather garlic mustard, please be mindful to not accidentally spread it.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts. Yes, it is a very complicated issue with room for multiple view points. People should indeed try not to spread it when harvesting, but honestly I think there’s a much great risk of spreading it by pulling it up. It’s great that you are replanting with native plants – that might help keep garlic mustard from re colonizing.

I’d also like to point out that so many of our food plants are maintained with pesticides which are potentially harmful to pollinators and other wildlife. Eating plants like garlic mustard that need no chemical assistance to thrive is reducing the demand for chemically maintained crops.

I am looking for information on violet leaves, how edible they are? I know about violets being added to salads and soup garnishes but how about the leaves? I find them very tasty but do not know if there is any toxicity involved in consuming large salad amounts. would you have any info on this? pls let me know…

yours truly

blissful gardener, Teresa

The only violets I’ve eaten are the common blue violet. I have eaten flowers and leaves with no ill effects. I’m not sure about eating them in large quantity, and that might be an individual thing, and might depend on how large a quantity. My friend’s son vomits if he eats too many raspberries, but I can eat at least twice as many with no problem.

I have this plant growing in my garden I am a native plant gardener but I do cut it down before it goes to seed because takes over your garden I have quiete a lot of it growing around my pond i like to see it growing where nothing else will grow in the shade its a lovely native in ontario Canada but some people call it weed !!!! I have eaten it with Egg saled its not bad.

Hi Joyce, I too enjoy it with egg salad! One thing, though. Garlic mustard is not native to Canada, either.

Pingback: To weed or not to weed… | DirtyGreenThumb

So much of this at the moment here (North Wales), can anyone give some tips on when to harvest the seed pods to make a mustard? They’re still green and not dried out

Mark, I don’t know the answer to that, because I haven’t tried it. I do know of 2 people who have tried making mustard with garlic mustard seeds, and both said they were not able to come up with anything palatable.

Love this post! I’ve shared it on my Garlic Mustard and Foraging Identification Pinterest boards.

One thing I would like to request, please be very careful when harvesting seeds–or any part of the plant when it’s in seed. They are small and can get on your clothes if you move through a patch, when you go to another area, they fall off and you can start new growth accidentaly. That can be a very bad thing with such an opportunistic invasive.

Good point, thanks Liz!

“Yet people destroy garlic mustard as a noxious weed” Those people are completely correct. Go ahead and eat it but for the love of all that is decent destroy this plant where you see it. If you don’t want the erosion of pulling please cut second years at the base before seeding. I promise you, if you kill every one of these you encounter for the next 20 years you will still find more. For those who are into gardening there are plenty of shade tolerant natives or edible, you may think no other plants grow in the shade, but that is because your garlic mustard plants release toxins that kill the fungi other plants need to sprout, garlic mustard isn’t the only plant that can grow there, it is poisoning the soil and killing other potential plants. This is not a harmless edible like burdock, dandelion, or creeping charlie, it is truly a destroyer of habitats. It is delicious mostly, but pretending it doesn’t need to be killed on the spot is dangerous, one plant releases thousands of seeds.

Thanks for sharing your opinion.

I fully agree. It is a very adaptive species as well. I can clear out an area full of it in the woods and it will still come back if not controlled. It also starts producing miniature copies of itself, very difficult to spot, that will also flower and seed. Natural selection at work I suspect.

That is an exaggeration, based on old assumptions and incomplete data. At least in some situations, garlic mustard has little to no impact, and accumulating evidence suggests it is “more a product than an agent of change in eastern North American deciduous forest”. See Davis, M. A. et al. “The Population Dynamics and Ecological Effects of Garlic Mustard, Alliaria petiolata, in a Minnesota Oak Woodland.” The American Midland Naturalist. 168 (2012): 364-374.

Note that in the discussion section of that paper, there is reference to 7 additional studies showing “very small, inconsistent, or no negative effects of A. petiolata on other plant species in eastern North American forests and woodlands.” See the list of literature cited in the Davis et al paper, for complete citations of those 7 papers.

Hi! Have you ever dried the plant out to use it at a later date? I have a TON of this throughout my yard and was curious about this. Thanks!

Nope, sorry, I’ve never tried drying it.

Pingback: Podcast 63 5 Rules for Foraging Wild Edibles + 25 Wild Edible Plants – Melissa K. Norris