Are you a practical person interested in sustainable farming and gardening? Practical Permaculture Principles might be just what you need.

This is an introduction to permaculture principles for those who want to implement them without a lot of philosophical pondering. I use a narrow definition of permaculture – a system of food production that mimics natural biologic systems – because it lends itself to concrete action. This may be very different from what you’ve been reading, but originally permaculture was narrowly defined. It was a blend of “permanent agriculture”, a biologic definition (1). It was later broadened to “permanent culture”, which ushered in ethical, social, and political dimensions (1,2).

As a result of the more generalized definition, a lot of the permaculture literature is quite broad and vague, with little discussion of the biologic. It can leave one wondering what permaculture is, and how to implement it in the farm or garden. Has that been your experience? If so, this is for you.

I’ve identified 9 properties of nature that permaculture seeks to mimic. They, along with their practical implications, are my permaculture principles. Hopefully, this will leave you with some concrete ideas for your own farm or garden.

To be clear, I am not a permaculture designer. I come at this from a background of conservation biology and forest ecology. It was within those disciplines that I learned about permaculture and agroforestry, a closely related topic. They make a lot of sense ecologically, so I incorporated most of the general concepts into our backyard farm, without ever thinking I was doing permaculture. Nature works, so why not mimic it?

Permaculture Principles: What does it mean to mimic nature?

In my examples I focus mostly on forests for two reasons: 1. I live in a heavily forested region (New England), and 2. Permaculture designers often focus on forest gardens (“food forests”). But there are other biomes on Earth, such as prairie grassland, savanna, and chapparal. One could theoretically base a permaculture garden on any one of those, and all of them are characterized by the properties described below.

1. Species diversity

The plant life of most natural systems is far more diverse than a bed of tomato plants. To see this, take a walk in the nearest forest. Stand still, and count the number of different kinds of trees, shrubs, vines, herbaceous plants, ferns, fungi, and lichen. Then consider the fact that each of those species attracts a unique suite of insects, birds, mammals, etc. Diversity of plants begets diversity of animals! One advantage to this is that insects with a preference for a particular plant species can’t all gather in one place for dinner, because the plants are spread out.

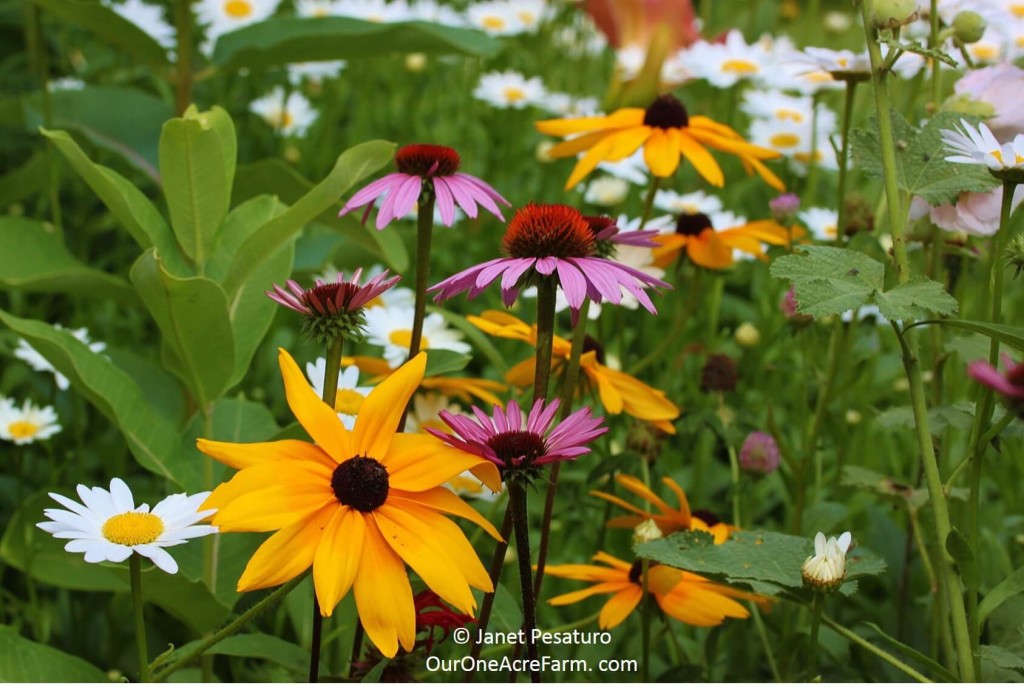

How you can mimic this for a permaculture garden or farm: Grow smaller amounts of a wider variety of plants and keep a wider variety of animals (if you have space). You can emulate this in your garden, but it doesn’t mean you have to give up your rectangular beds. There’s no need to be a fanatic. Instead, you could apply the concepts in a way that’s reasonably convenient. How about rows or groups of several different vegetables in each bed? Maybe throw in some flowers, too.

Our perennial garden is packed with different species, some native and some non-native. It attracts a diversity of insects including pollinators, and stands close to some fruit and nut producing shrubs and vines.

2. Symbiosis

Symbiosis refers to the close interactions between species, which speaks to their interdependence. They don’t just live near each other, they interact, and sometimes depend upon these interactions. Permaculture gardeners sometimes call these symbiotic relationships connections. Here are some examples of symbiosis in nature:

- Many trees need specific soil fungi associated with their roots in order to grow well. The fungi provide phosphates and nitrogen to the tree while the tree, in turn, provides carbohydrate to the fungi.

- Legumes do better with certain soil bacteria (rhizobia) which become established in their root nodules and fix nitrogen.

- Insects feed on flower nectar, and pollinate the plant while feeding.

- Birds and mammals feed on fruits and berries, and later excrete the seeds with a dollop of fertilizer, assisting reproduction of the very plants they need for food.

How you can take advantage of symbiosis: Learn about companion planting (3), wherein mutually beneficial plants are grown together. Permaculture gardeners develop the concept of companion planting even further, and call mutually beneficial plant groupings “guilds” (4). Grow some companions or plant a guild.

As insects harvest nectar and/or pollen , they pollinate the plant. This is a classic example of symbiosis.

3. Balance

This is largely a consequence of diversity. Creatures which feed on plants are kept in check by other species – they tend to stay in balance. A diverse group of plants provide a variety of food and micro habitats for a variety of animals. All of these plants and animals together form a complex food web, with every species a featured menu item for at least one other species. Thus, outbreaks are uncommon. Some examples:

- Foxes eat rabbits and voles, thereby limiting the damage done to plants.

- In the western US, wolves keep elk from over-browsing trees, so other herbivores, such as beavers, have enough to eat. And beavers, in turn, create habitat for many other species, as you can read in Beaver: Appreciating Nature’s Other Engineer.

How you can encourage balance: Grow a diversity of plants (and animals, if you can) provide food and habitat for native wildlife, and try to tolerate wildlife even when it’s inconvenient. Here are many ideas for plants that attract native wildlife:

- 15 Trees for a Wildlife-Friendly, Edible Landscape

- 10 Shrubs for a Wildlife-Friendly, Edible Landscape

- 12 Native Plants for Food and Medicine

- Gardening for Pollinators

If you do notice a pest outbreak, learn what you can do to restore the balance without resorting to warfare.

Eastern coyote photographed by camera trap. The debate over whether coyotes are native or not, and whether they are “good” or “bad” might never end. But I choose to tolerate them, and appreciate their expertise in rodent control. Tolerance for wildlife is am important part of sustainable living.

4. Redundancy

In natural biologic systems, several different species might overlap in function. Such redundancy makes the system more resilient, for if one of those species is lost, its function will not be totally lost. For example, bobcats, foxes, coyotes, and great horned owls all eat voles, mice, rabbits, and grouse, here in my Massachusetts suburb. If we lose one of the predators, we are not likely to see a population explosion of the prey species, because several other predators will still be eating them.

How you can apply the concept of redundancy to a permaculture farm or garden: As one example, plant several different greens, rather than just spinach. If the spinach does not grow well, you will still have other greens to eat. Growing several different types of greens also adds to diversity beyond the dinner table. The different species will attract different types of insects, and take up soil nutrients in different proportions.

I love seed mixes, like this mix of baby salad greens. Growing a variety of plants that serve the same purpose and overlap in nutritional profile is one way to confer resilience to your food production system.

5. Vertical structure

Many natural systems are composed of plants of many different heights. This is easy to see in some forests, especially mature ones. Beneath the canopy of large trees are smaller trees, shrubs, vines, herbaceous plants, and ferns. Together, they give the forest what we call “vertical structure”. Complex forest architecture attracts a diversity of animals. For example, some birds need tall trees from which to sing out territorial occupancy. Other birds nest under the forest canopy in shrubs. A habitat with multiple “layers” of vegetation generally carries a greater diversity of animal species, than a forest, farm, or garden, composed of one monotonous layer.

How you can create a higher degree of vertical structure: Include fruit and nut trees, berry producing shrubs, and annual and perennial vegetables in groups within your edible landscape. In permaculture, this is called “stacking”. Another idea is to use climbing structures to allow crops like beans, squash, and peas to use vertical space and create vertical structure.

Adding trees and shrubs to your garden creates vertical structure. We have a clump of apple trees, blueberry bushes, and hazelnut bushes near the vegetable garden. This clump is also great cover for our chickens, just as dense vegetation is great cover for wildlife.

6. Plants grow where their soil, light, and moisture requirements are met naturally

And it happens without back breaking or energy guzzling human intervention. No one is spreading Miracle Gro, nor watering. If you can mimic this, you’ll save yourself work and fuel.

How you can emulate this: There are two paths you can take. First, you can plant according to the existing conditions on your site. What are the soil characteristics, sun exposure, and moisture levels? Do you have a naturally moist area? Grow plants that need a lot of water. Dry, sandy soil? Grow more drought tolerant plants. Second, you can change the conditions to grow plants you want. Poor soil? Grow nitrogen fixing plants to enrich it. You can even change the topography of your land, by creating a swale for example, so that water will go where you want it. Want to grow plants that need dappled shade? Create shade by planting a tree.

We planted some native flowering dogwood for their beauty and wildlife value. An understory tree in the wild, this tree prefers the shelter and light shade of taller trees. Ours struggled out in the open, until the neighboring beeches grew up to provide some shelter. Now they are thriving.

7. Succession

Natural communities are always changing, and when soil, light, or moisture requirements are no longer met, plants will die, and other species take over. Plants grow, reach their maximum height, and eventually die. When one dies, more sunlight, water, and soil nutrients are available for its neighbors. This process of change in species composition over time is called succession.

Succession is most easily visualized in a forest, where the different types of plants – trees, shrubs, vines, and herbs – are easily distinguished. Consider a new forest growing up in a recently cleared area. First, sun loving herbs, shrubs, and trees begin to grow. As the sun loving trees grow up, they shade out some of the smaller plants, and shade tolerant plants begin to fill the understory. Eventually, the sun loving trees will die, and the shade tolerant trees will dominate. Still later, they too will die and fall over. That will create gaps in the tree canopy, allowing sunlight to reach the forest floor, so that sun loving plants can once again thrive. In this way, forests are always changing.

This is quite different from the usual concept of a farm or garden. We fight to keep it the same, year after year. A plot of annual vegetables is always a plot of annual vegetables. An apple orchard is always a grid of apple trees. But it doesn’t have to be this way. Nature shows us that mixed groupings can be rich with life if change is tolerated.

This wild highbush blueberry fruits well in light shade, but won’t fruit as well when neighboring trees grow taller. But by then, the oaks and hickories will produce more nuts. Forests are always changing, and the crops they produce change accordingly.

How you can allow for succession in your landscape: Grow layers of food producing and wildlife attracting plants, including trees, shrubs, vines, and perennial vegetables, in addition to the usual annual vegetables. Some plants will yield food almost immediately, while others won’t yield for several years. Some may eventually shade out other food plants when they are large enough to yield. Expect change, and plan to accept it and work with it.

8. Recycling: soil building from within

Let’s take a temperate forest. How is the soil built? Leaves of deciduous trees and shrubs fall to the ground, and herbs die back every fall. Dead branches and trees fall to the ground. Animals poop, and eventually they die. Most of this organic matter is left to decompose, with the help of soil borne organisms, because no one rakes it away. And some plants fix nitrogen from the air. Soil is built without fossil fuel intensive synthetic fertlizers.

How you can mimic this for sustainable farming or gardening: Use organic matter produced right on your property for mulch and compost to build the soil.

Manure from our chickens is used for soil building in our backyard. Poopy litter goes into the compost, or right onto a bed as mulch. In October, the chickens get the run of the vegetable garden, and here they are “helping” me prep a bed for garlic, scratching and pooping as they go.

9. Minimal tilling

In natural systems, the soil does get aerated, but not by the plow. Earthworms and burrowing mammals slowly and subtly till and aerate as they tunnel. A plow, on the other hand, results in far more oxygen exposure, which releases nutrients much more quickly than plants can use them. It also destroys soil structure, which results in erosion.

How you can rely on natural soil aeration: Use one of the no-till garden methods, such as a lasagna garden (5) or hugelkultur (6). Both involve layering organic matter which keeps down the weeds, making tilling unnecessary.

This hen is standing on an untilled bed mulched with dirty hay from the chicken run.

Examples of permaculture farming and permaculture gardening

- Shade grown coffee borrows from permaculture. Coffee “trees” grow as shrubs or small trees, reaching only about 12 feet. When coffee is grown as a monoculture (“plantation grown”), it is prone to serious pest problems, requiring pesticides to thrive. But in the wild, coffee thrives as a forest understory plant. Shade growers mimic its natural habitat, by planting it under a light canopy of a variety of tree species. The tree roots help reduce soil erosion, the shade helps retain moisture, and the plant diversity and vertical structure attract a much wider variety of animals. The diversity of insects mean better pollination, and the diversity of birds, mammals, and lizards keep the insect pests in check (7).

- Aquaponics combines fish or other aquatic animals grown in tanks, with hydroponics (growing plants in water). Water containing the animal excretions is fed to the plants, which take up the nutrients, cleansing the water. The water can then be returned to the tanks, and the cycle continues. This system the mimics the natural symbiotic relationship between aquatic plants and animals.

- Three sisters garden: Corn, beans, and squash are are mutually beneficial when grown together. The corn stalks are structural support for climbing beans, which enrich the soil by fixing nitrogen. The corn and squash benefit from the increased nitrogen. And the squash plants shade out weeds.

A Three Sisters Garden at King’s Garden, Fort Ticonderoga, NY.

Sources

- About Permaculture, By David Holmgren

- What is Permaculture?

- An In-Depth Companion Planting Guide

- Using Fruit Tree Companion Planting and Animals in Permaculture Guilds

- Lasagna Gardening

- Huglekultur

- Shade Grown Coffee

Feel free to share your own thoughts, experiences, and questions about permaculture in a comment below!

I enjoyed this article. Very informative!! Thank you!

You are most welcome, Darlene. Glad you found it useful!

Excellent post! You answered so many of my questions about this “permaculture” idea I keep reading about. Thanks for providing great tips on ways we all can begin to implement these concepts. 🙂

Thank you so much, Rebecca. I found a lot of the current material on permaculture too obscure, so it became my mission to make it clearer and more useful.

Lovely post as always!

Aw, thanks, Amber!

Thank you so much for posting this article. I had been pretty confused as to what permaculture was in practical terms. Many thanks!

Sarah

You are welcome, Sarah, I’m glad you found it helpful!

Pingback: April Showers Bring May Flowers | locallygerminated

Very informative article. I’m in the process of completing a PDC now and this makes it sound very simple becasue we need to work with nature. A lot easier than always fighting nature.

Thanks, Jim, I am glad your found it helpful. I’d love to take a PDC myself sometime. I simplified permaculture greatly here, as I’m sure you realize. I’d love to learn the nuances.

Simply desire to say your article is as amazing. The clarity to your put up

is just great and that i can suppose you are a

professional on this subject. Well with your permission allow

me to seize your feed to keep updated with imminent post.

Thank you a million and please keep up the gratifying work.

Very clearly written – one of the best posts I’ve read. How would you relate permaculture to “sustainability” as in the Sustainable Sites Initiative? I think, as you have described very nicely, permaculture principles can be applied to non-edible landscapes as well as agricultural ones. After all, if we’re doing it right, it’s all going to be edible to something, no? But there seem to be 2 camps – those that relate to permaculture and those that relate to sustainability. Yet they’re really talking about the same thing.

Interesting, LB, I hadn’t really thought about it in terms of 2 separate camps, but perhaps you are right. I do agree that generally speaking, they are talking about the same thing. They might quibble over some important specifics, though, and permaculturists, imo, tend to be focused more on human use than on wildlife benefits. For example, permaculturists tend to embrace non-native species, even those which are invasive, as long as they are useful to humans. But many people concerned about sustainability shun them because they can dramatically change wildlife habitat to the detriment of certain species (like native pollinators). Also, permaculture in the broader sense (with the political, ethical, and social dimensions) appeals to a specific group who share those views, whereas people promoting “sustainability” come in all flavors of political, ethical, and social views. Glad you enjoyed the post!

Pingback: Guide to Growing Sunflowers - One Acre Farm

Pingback: Permaculture Principles For Practical Gardeners & Farmers

Pingback: How to Start a Backyard Farm - One Acre Farm

Pingback: Growing and Using Greens for Salads and Cooking - One Acre Farm

Pingback: 8 Reasons to Grow Daylilies - One Acre Farm

Pingback: Limited Free Range Chickens: 12 Tips to Balance Freedom & Safety - One Acre Farm

The Protected by DCMA just made me laugh and think… Can I really take this seriously?

It’s DMCA. Makes all the difference. You’d be amazed at how often blog posts are scraped. It happens all the time.

Seems like Biomimicry would be something you’d be interested in reading more about if you are unfamiliar with the concept! It’s pretty science heavy and closely related to permaculture imo.

Yes, Kaitlin, I know what biomimicry is and its relationship to permaculture. Perhaps you didn’t read it carefully enough to notice that throughout it, I spoke of mimicking natural systems. I wrote this piece for people struggling to understand how they can apply the concept of permaculture to their own backyards, and didn’t feel it necessary or desirable to load up on technical terms. Even as it is, it may be a bit too much on the nerdy side for the audience I had in mind.

Pingback: How to Grow Apples Without Pesticides - One Acre Farm

It is wonderfully written practical guide for beginners like me to start a project in India. I feel greedy, won’t you write more please? But thank you very much for what you have already given. Regards.

Thank you, Shantanu, I haven’t been posting much lately, but will get back to it soon. And good luck with your project!

Pingback: The Best Homesteading Articles and Books of 2015 | North Country Farmer

This was most excellent.I too have a background in wildlife biology and ecology. I was at first excited about permiculture then dismissive when it became difficult to sift through the political/social aspects to get the clean farming guidance I wanted. Only three years later have I come back to it and realize its potential. Thank you for posting this and getting the permaculture word out there for us practical folks.

Thanks for the kind words, Mary, I’m so glad you found it useful. Happy farming!

I tried the 3 sisters in my garden and it was a disaster. I couldn’t harvest anything because of the other 2 plants. The corn was so tightly tied to the stalks by the vines I couldn’t get it free, The beans were out of reach without stepping on squash and I gave up on the squash because of the walls of cornstalks and bean vines. I also tried a highly-recommended combo of corn and potatoes but couldn’t dig the tubers without uprooting the corn. The only combination I have really liked was beets between green beans. I also plant four-o-clocks in the middle of my green bean area – it definitely keeps the bugs off the beans.

It probably depends on the varieties of corn, beans and squash you use. Native Americans were not using the hybrids we use today. Also spacing is probably critical.

Very informative

Very helpful post! Definitely very helpful information on permaculture method. I’m considering to try this few years already and finally started my permaculture garden this year. Found some really good ideas and advises here. Thank you for sharing and happy gardening!

You are very welcome, Jennifer, and good luck with your gardening!

I love reading all of your articles, you are very knowledgable! Your posts have been helping answer a lot of questions that I had about my chickens and about gardening. I started my first small vegetable garden in my backyard but I am having trouble. For example: the label on the packet of seeds for the radishes specified that they will be able to be harvested in 4 weeks but I have had them in the ground for about 7 weeks already and they are not ready to be harvested. The same situation with my onions and carrots. I am completely new at this and would appreciate your help please! Thank you for your posts, they keep me very interested for hours!!

Hi Alondra, I’m glad you find my blog useful! It’s hard to say what the problem is with your radishes, without knowing more about your climate, soil, etc. Off the top, I wonder if there is too much nitrogen in the soil. That can cause lush greenery at the expense of root development. Inadequate sun exposure can also slow growth. Also I will add that sometimes you just can’t take the expected time till harvest too literally. My carrots always take longer, for example.

Simple,uncomplicated,uncommercialized,common-sensical version/form of permaculture education.

Thank you, that was exactly my goal!

Wonderful easy to read guide. Thank you!

Pingback: The Best Ways To Expand Apples Without Pesticides |

Informative. Thank you.

Pingback: What is Permaculture? Designing a Resilient Garden - Internationalgbc